Selvas tengo en el corazón; árboles gruesos prietos de ramas; yuyos, retamas, flores de malvón, pájaros en las ramas, todo eso tengo en mi corazón.

– Alfonsina Storni

Una chica de ciudad. I once was a city girl. Coming from a small Spanish city, I grew up seeing only pigeons and storks around. The Plaza Mayor was infested by temerarious, dirty pigeons fed by the old men who would sit in the benches throwing crumbs absentmindedly to those aviary pests. I don’t remember seeing many storks flying around though, but their huge nests on top of San Lesmes bell tower were a reminder of their existence.

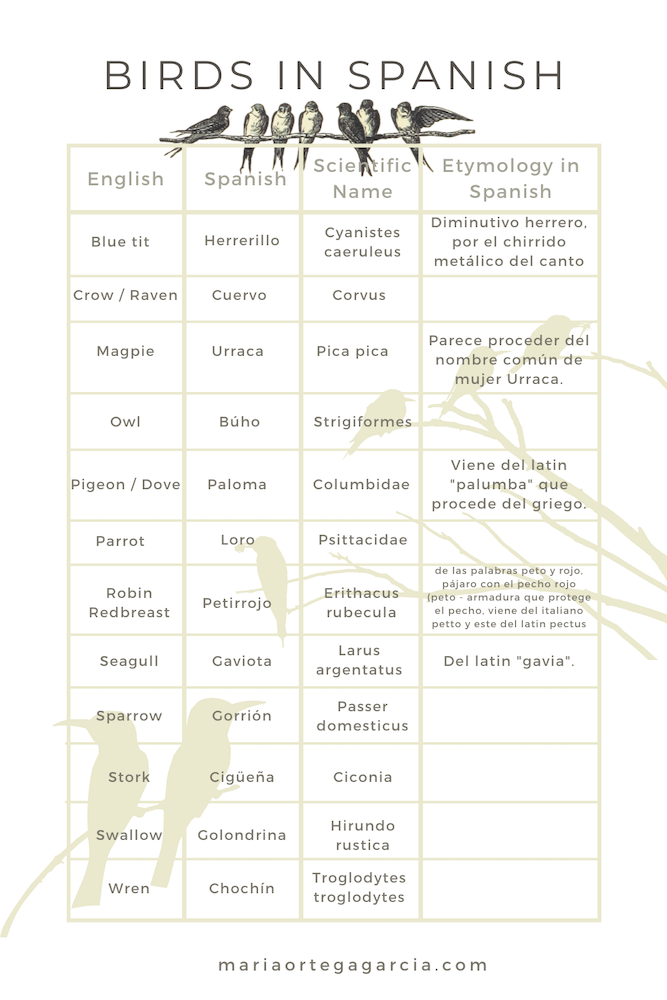

The names of birds in Spanish were empty words, devoid of real meaning to me. I knew names of birds that I identified as birds but had no idea of what kind bird they were because I’d never seen them in real life. Vencejos, tordos, chochines, herrerillos… (Note: at the end of the post there is a list and translation of all the bird’s names that appear in this article) were words I knew belonged to the category of birds, although I don’t even remember where I learned that information. Ciencias naturales (natural sciences) subject in school, maybe? In any case, those words had no meaning. Had I been ambling around in a forest and saw a “vencejo” perched on a branch in front of me, I’d had no idea what that bird’s name would have been. There was no connection between the word and the reality of it.

Of course, I had some images in my mind, I knew what a loro was because I had seen funny videos of parrots cursing, or I intellectually knew what a cuervo or a búho were. But they were like the concept of “peace” or “angels”, notions that are either abstract or something I can understand but I don’t really grasp because I’ve never experienced through my senses.

Names like garza o herrerillo were just that. Names. I had not the faintest idea of what they looked like, how they lived, their habits…

Other names like urraca, gorrión o golondrina were more familiar, not because I had seen any of their specimens in real life, but because I had read poems about them, so I knew that people normally like “gorriones” and “golondrinas”.

Volverán las oscuras golondrinas

en tu balcón sus nidos a colgar,

y otra vez con el ala a sus cristales,

jugando llamarán

– Bécquer

Or the opposite, the bad image “urracas” ge as thieves that steal any type of shiny things. Had I ever seen any urraca? Nope. Did I dislike them just because of that passed on idea? Yep.

But at least, urracas had a deeper meaning. They meant something beyond the word itself because I had experienced them through someone else’s artistic expression or through folklore.

Experiential Learning

It was when I moved to Ireland that the name and the related object, in this case, bird, started to be connected. And then seagulls also started to be a part of my experiential knowledge. I knew what they looked like, and the noise they made. I learned what it means to see them in large numbers squawking away inland as harbingers of storms or bad weather.

Then, when I moved away from Dublin city to a small town in the south-east of Ireland, to a house with a little garden, things started to change.

Blue tits, sparrows, wrens, robins, magpies, crows and ravens are a daily occurrence.

By virtue of seeing them repeatedly and having been given their names, I (my brain) developed the connection between the real instance of the bird and its English name. No study involved.

Now, I can distinguish them and we have even struck up a relationship. Crows craw “hello” every morning when they alight on the telegraph pole near my house, or when I pass by any green area in the neighbourhood. I learn how they gather and fly together to find a suitable tree for the night. I am friends with the single robin that visits us regularly to have breakfast and lunch from our feeder and I can now spot robins easily. I learned that, unlike the sparrows, robins are territorial, so they defend their space ferociously. And I am delighted that my garden is part of a tiny Robin territory.

A tiny blue tit and a bunch of sparrows visit every day and flutter about (revolotear) the garden. They search for insects or get peanuts from our feeder. The birds are now the avian side of our family. My heart melts remembering the warm evening nights last summer when they, the sparrows, would have daily dust baths on the swept pile of dry dirt in one garden corner.

Experience is embodied cognition.

The birds I am sharing my life with, exist in English in my mind despite me being Spanish. Despite my ample vocabulary of birds in Spanish and despite these words living in my brain before the English version. When I see a “passer domesticus” (specific name for sparrow or gorrión) my brain recognizes the type of bird and it gives me a name: “sparrow”, not “gorrión”.

Because the key to learn something, anything is to experience it, to live it. We cannot experience or live without our bodies. Our minds are not isolated, they are embedded in our bodies, through which we perceive and act. It is through perception and action that our brains store information.

Let me support this idea with an article that appears in NCBI National Center for Biotechnology Information) entitled: “Embodied Learning: Why at School the Mind Needs the Body” written by Manuela Macedonia:

“In fact, neuroscientific studies have demonstrated that processing of objects, spatial information, music, faces, flavours, odours, and also mere thinking of these concepts evokes sensorimotor responses, i.e., body-related activity in the brain. This relies on prior experience connected to manipulating objects, moving around, eating and smelling things. Areas and brain structures involved in the process wire together to networks of neurons that represent and store the information.”

May my heart always be open to little

birds who are the secrets of living

whatever they sing is better than to know

and if men should not hear them men are old

– e.e.cummings