Trauma and mental health informed language educator

The concept of trauma and the need for a trauma-informed practice are rapidly gaining recognition. As a self-employed or private language teacher, it’s crucial to understand the necessity of being informed about trauma and mental health in your profession.

You may be thinking that being patient, friendly and open-minded is enough. And while those personality traits are definitely important, they are not enough. The good news is that what is necessary to work with people in the relationship “learner-educator” is not personality traits but skills everyone can develop.

You may be wondering if learning these skills around mental health and trauma is actually necessary, and you may be thinking:

But I only work with adults

But I only work with kids

It’s crucial to understand that around 70% of people globally will experience a potentially traumatic event during their lifetime, and 60% of people around the world are estimated to have experienced at least one form of childhood adversity (ACE). This prevalence underscores the urgent need for trauma-informed practices in all educational settings, including independent language teaching.

You may be thinking that you are purposefully not touching potentially triggering topics, avoiding having emotionally charged conversations and focusing only on the positive during the class. Awesome! Now, what if you don’t identify a topic as potentially triggering? You may think that talking lightly about family or culture is safe, but is it? For everyone? Could there be any cases where talking about parents could be painful and evoke triggering memories or experiences? Could there be any instances where talking about the learner’s culture of origin could be painful, or even about certain aspects of the culture of the target language?

You may think that you are a nice, friendly teacher, not a super strict, prone-to-anger teacher like the ones in school, so your learners must feel safe with you. Do you know how the learner feels when you ask them a direct question? How do you feel when there is little to no progress, no personal work outside classes or no interest in the language? How do you feel about the learner when they make the same mistake over and over? Do you know if the learner can perceive when you are angry, frustrated or stressed out?

Being informed about mental health and trauma is for every professional who works with people, but mainly for those in a position of authority (all educators). Having a trauma-informed teacher benefits:

Those students who have identified their language or learning is connected to trauma.

Those who haven’t identified it yet, but it is impacting their language learning outcomes, either during the learning process or by defining themselves as “bad in languages” so they don’t even start to learn a language.

Those who haven’t experienced trauma in relation to language or learning but have experienced trauma in other areas of their life.

Those who haven’t experienced trauma at all.

You may even be thinking that learners do not seek a trauma-informed teacher; it’s not needed, and they don’t identify being trauma-informed as a skill required. I used to believe that. I still wanted to learn because I, as a teacher, identified it as a need, but no learner had directly asked me if I had the skills to work with a learner with trauma until a couple of months ago.

I had a consultation with someone who wanted to learn Spanish with a trauma-informed, qualified teacher. She was aware of her trauma and was working with a therapist about that. Still, she also knew that because her trauma was connected with her heritage language and culture on her father’s side, she’d benefit from working with a teacher with whom she could feel safe in case some intense emotions arose.

Even if this student was just one person, my learned skills about mental health and trauma came in very handy when a learner broke into tears after I corrected a little misspelling. Through therapeutic conversation, I learned that her parents were very, very strict and that she attached her worth to academic success and perfection, so one simple mistake could quickly shake her to the core. Or when another brilliant student would be unable to speak in the target language but wrote the most complex essays, through building trust and therapeutic writing, I learned of the abuse she suffered from a tutor and bullying from her schoolmates.

Being trauma-informed goes beyond being open-minded.

It requires nonjudgmental curiosity and empathy.

That is healing.

Desmond Tutu’s sentence, “If you are neutral in situations of injustice, you have chosen the side of the oppressor,” comes to mind.

If we do not feel we can do something when someone (our student) is suffering from a physical or mental illness, what are we doing? If we are not helping, what are we doing? What kind of relationship are we fostering?

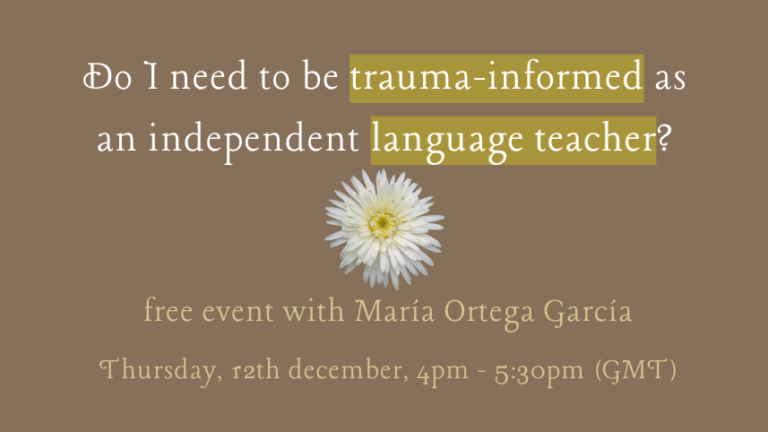

In this free event, I will address the following questions and provide practical strategies and resources for implementing trauma-informed practices in your language teaching:

Do I need to be trauma-informed as a language teacher if:

I only work with adults?

I only work with kids?

I only do one-to-one classes?

I only work with groups?

What is trauma, and how can it appear in the class?

Education and trauma: What is educational trauma, and how can it affect our adult learners?

Language and trauma: How can learning/speaking a language be triggering? For example, (re-)learning a mother tongue or heritage language, language anxiety, etc.

How and why do we start creating a psychologically safe class environment?

What do I need to start providing therapeutic interventions and mentally healthy practices in my classes?

Thursday, 12 December, 2024.

4pm – 5:30pm (GMT)

Online

(Recording will be sent to all signups)

¿Qué prefieres asistir a este evento en español? No hay problema, dirígete aquí para apuntarte.